I wrote a Twitter post at the weekend that caused a bit of a stir.

Like any good post optimized for engagement, a lot of the respondents got very riled up and called me rude names. In some software engineering circles, it was not highly regarded.

The most basic form of this response was essentially "LLMs can't (and will never) write real production-grade code."

A slightly more sophisticated version was "as the cost of producing code goes down, the demand will rise exponentially, and so the total market for code-writing will actually expand." And the demand-side of low-cost, high-quality software is practically unlimited, unlike food.

Haven't you heard of Jevons' paradox?

I want to address these two points in order, but a quick note about my intentions first.

I think that technological progress truly offers a path to a better world for all of humanity; I dream of a future state of shared abundance.

Technology clearly accelerates human progress and makes a measurable difference to the lives of most people in the world today. A simple example is cancer survival rates, which have gone from 50% in 1975 to about 75% today. That number will inevitably rise further because of human ingenuity and technological acceleration.

Of course those benefits aren't shared equally around the world. A point I will return to later.

I also love software engineering and building things. I have spent my entire career on it. I don't want software engineers (or anyone, really) to lose their jobs. It's an incredibly painful process and I think it will result in extreme societal disruption.

This is the central point I'm trying to make: Technological progress is accelerating very rapidly and I don't think most people are prepared for that future.

Ok, so let's take the two points in order.

LLMs aren't (and never will be) good enough to replace X.

ChatGPT was launched at the end of 2022. Anthropic's Claude was launched in March 2023. We had GPT architectures before this date, but I'd argue this is when the technology became readily available to most people. Early adopters jumped on it and quickly realized that hallucinations were rife and the answers weren't always useful as a result.

That was about two years ago. The progress since then has been nothing short of astonishing. Gains in AI are accelerating much faster than Moore's Law.

The progress in coding-specific models in the last few months alone has been wild. With Claude 3.5 Sonnet's launch in June 2024, Anthropic explicitly targeted agentic coding and tool use, and that investment has paid off.

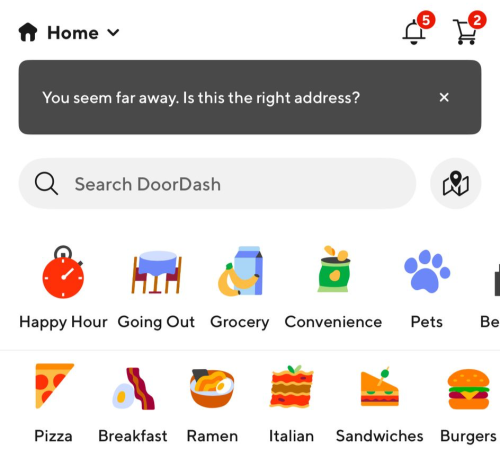

Today, tools like Windsurf, Cursor and Claude Code feel like they give professional software engineers superpowers. Tools for non-developers like Lovable and Replit Agent aren't far behind.

Gemini 2.5 Pro was released just days ago, and already seems to be another step up. Cursor and Windsurf are already scrambling to incorporate this new model into their product.

People who tried and dismissed AI coding products even six months ago need to re-evaluate their assumptions. Last month, I probably spent 80-100 hours using these tools. They are genuinely astonishing.

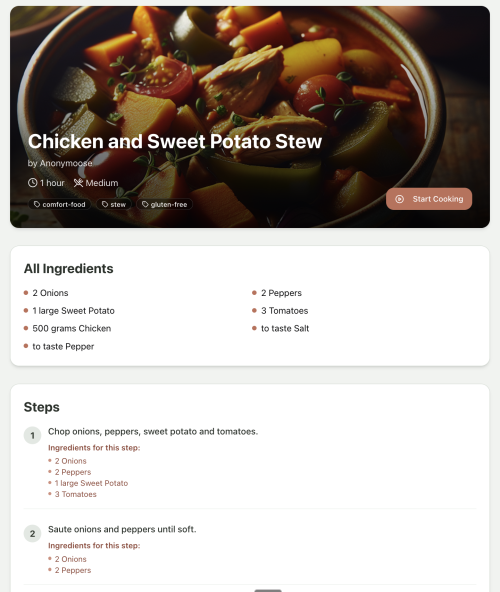

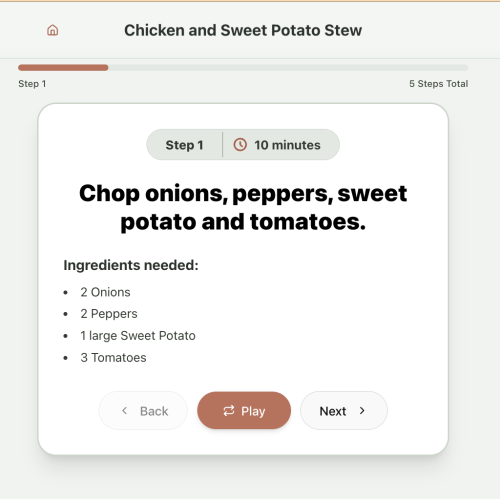

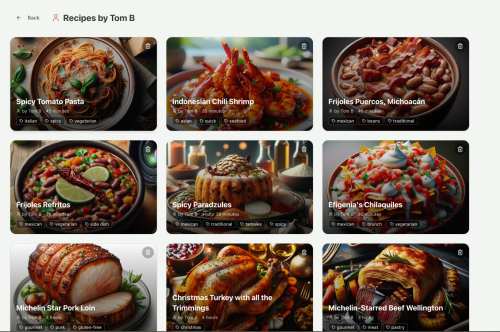

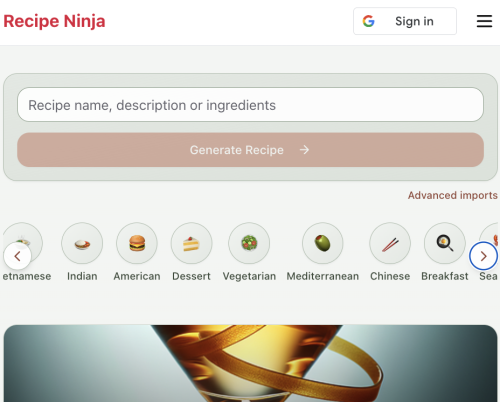

I rebuilt my personal blog, set up hosting and domains and migrated it from Tumblr, all in a couple of hours. I built RecipeNinja.ai and incorporated an interactive voice agent that will generate recipes and navigate around the site for you. It's about 35,000 lines of code; every single line was written by AI. It is still a relatively small project, but one that would have taken me several months to hand-code. I've also built a number of other personal tools and games. I am easily 10x more productive with these new tools.

I know the immediate response will be "that's just a small toy project, you don't have any experience as a professional developer on large, legacy codebases." I don't want to spend too long trying to convince you of my nerd credentials, but I founded and coded most of the first version of gocardless.com (alongside @harrymarr and @hirokitakeuchi) before founding monzo.com. I have been part of some very large software projects.

Here's the thing; a single human can't understand a 10M-line software project on their own. And so they break it down into composable modules, test and document each part separately. Then you can reason about the modules at a higher level of abstraction. That's how AI will deal with larger codebases too.

These coding tools seemed like toys, but that is how every new product feels at the start. The complaints that the coding tools routinely expose private API keys in front-end code or don't write scalable production-ready code were absolutely true at one point. But that has not been my experience in the last month.

These tools are now very good. You can drop a medium-sized codebase into Gemini 2.5's 1 million-token context window and it will identify and fix complex bugs. The architectural patterns that these coding tools implement (when prompted appropriately) will easily scale websites to millions of users. I tried to expose sensitive API keys in front-end code just to see what the tools would do, and they objected very vigorously.

They are not perfect yet. But there is a clear line of sight to them getting very good in the immediate future. Even if the underlying models stopped improving altogether, simply improving their tool use will massively increase the effectiveness and utility of these coding agents. They need better integration with test suites, browser use for QA, and server log tailing for debugging. Pretty soon, I expect to see tools that allow the LLMs to to step through the code and inspect variables at runtime, which should make debugging trivial.

At the same time, the underlying models are not going to stop improving. they will continue to get better, and these tools are just going to become more and more effective. My bet is that the AI coding agents quickly beat top 0.1% of human performance, at which point it wipes out the need for the vast majority software engineers.

In the near future, I can imagine a software team that is entirely composed of AI agents. You will have a long-running "product manager" or architectural agent that sets the direction of the product and breaks it down into individual steps. Individual coding agents will take tasks and execute them before passing the code over to a QA agent that tests it against a set of pre-written integration and user-acceptance tests. You may have specific agents that review everything for scalability and security and then pass suggestions to the product manager. Once the software is live with customers, any feedback will be sent into a customer service agent which will distill it and pass it back to the product manager. These recursive, iterative loops will happen thousands of times an hour, 24 hours a day.

Of course there will be human review of and guidance of these iterations, at least at first. But at some point in the next five years, I expect some (obviously not all) coding teams to be entirely self-directing. The idea that a human will need to handwrite code in future will seem very quaint. People might still do it for fun, just like we drive classic cars today.

Of course, it will take some companies longer to adopt the AI coding tools; folks who are sensitive about exposing their codebase or data to OpenAI or Anthropic for whatever reason. Companies will be reticent to trust the AI with very large, mission-critical codebases - like banks or spacecraft for example. But I think even that will change as the AI proves itself to be better than human developers over time.

"The AI will never be good enough to write real production code" is clearly a losing proposition. From a survey of my Twitter replies, that argument seems to be made by software developers who are scared and angry about the prospect of losing their jobs.

If you are a professional software engineer, I strongly urge you to spend 10-20 hours getting up to speed with the latest tools. I don't know if they'll offer much protection in the long-term, but they are going to make you dramatically more productive this year.

Jevons' Paradox will save us.

A more sophisticated objection than "The AI isn't smart enough to code" is Jevons' paradox.

Jevons' paradox states that as technological progress lowers the cost of a resource, consumption rises. That greater demand ultimately offsets—or even exceeds—the initial cost reduction.

Other people noted that the potential demand for low-cost, high-quality software is much greater than the demand for a physical resource like food. We can only consume so many calories, but there are always more problems to solve with software. Perhaps my farming metaphor was poorly chosen.

I agree with that entirely. I think we're going to have a lot more software in the future. Normal, non-technical people will be able to summon up a new custom-written software program to solve a trivial daily task much the same way they might use a spreadsheet to make a list or do simple sums today.

Here's the problem. That increased demand will be met with increased supply -- from rapidly scaling AI. I just don't think there will be any point in a human writing code for very much longer. My guess is that AI will soon be provably and obviously better at basically every facet of it. We will still have senior software engineers supervising the AI for many years because it makes humans feel safer. But they will eventually be like the conductors on self-driving trams; they are mainly there to make people feel better. This is the point that makes software engineers really angry, I think.

I think once we hit the tipping point where the AI is provably better at a given job, the societal change will be very, very rapid. I prefer self-driving Waymos over Uber or Lyft today. They're abudant in San Francisco and they're awesome. Data shows they cause 81% fewer injuries than human drivers. Put another way, humans cause 5x more accidents driving the same distance in these same cities. The technology is clearly better than humans today.

However, the global rollout of self-driving Waymos is slow because Google has to manufacture millions of very expensive self-driving cars equiped with LiDAR. The rollout of AI for knowledge work doesn't have those physical constraints in quite the same way, although the main bottlenecks in the medium term are going to be energy supply and GPUs. Closing a call center to replace the team with AI service agents will take a handful of days.

I think software engineering is just the canary in the coal mine. These same advances will happen across all knowledge work - doctors, lawyers, accountants, auditors, architects, engineers. The cost of accessing world-class medical or legal advice will come down to a $20/month subscription to OpenAI or Anthropic. There are already thousands of examples of people solving their own medical issues or getting legal advice from AI where expensive human professionals have failed. I'm not saying the AI doctor or AI lawyer can replace humans today - of course not. I am saying it is practically inevitable that the AI becomes better than humans at these jobs given enough time. That time period is shorter than most people believe.

In the short and medium-term, I can see service-heavy industries like boutique lawyers, doctors, accountants, or wealth managers actually becoming more profitable. I think they will be run by a small handful of senior partners, with the back-office administrative staff replaced very quickly with AI. Existing clients, especially older clients, will still prefer face-to-face human contact, so I think that senior partners in these industries are protected for 20 years until their client base dies off. But I think that the junior and mid-level lawyers, paralegals or accountants who are doing the bulk of the actual work are going to quickly bear the brunt of job losses.

To counter some obvious objections; clearly, physical work is protected for now. We will still need medical technicians to take readings from medical devices or surgeons to perform procedures. I think robotics is probably 10 years behind AI and the rollout will be much more constrained by physical manufacturing. But that's a topic for another blog post.

Some industries will have gatekeepers. Professions like medicine and law are highly regulated, and they're not going to give up the keys to the kingdom that easily. Regulators will likely insist a human doctor signs a prescription for medicine, even if the AI is writing out that prescription. It's like the conductor on the tram.

We're already seeing this

About a quarter of the recent YC batch wrote 95%+ of their code using AI. The companies in the most recent batch are the fastest-growing ever in the history of Y Combinator. This is not something we say every year. It is a real change in the last 24 months. Something is happening.

Companies like Cursor, Windsurf, and Lovable are getting to $100M+ revenue with astonishingly small teams. Similar things are starting to happen in law with Harvey and Legora. It is possible for teams of five engineers using cutting-edge tools to build products that previously took 50 engineers. And the communication overhead in these teams is dramatically lower, so they can stay nimble and fast-moving for much longer.

The big tech companies have dramatically slowed their hiring of entry- and mid-level software engineers and data scientists in the last year.

So what?

I think we face a future that is both amazing and incredibly frightening. Anyone who can afford a subscription will have access to extremely high-quality knowledge work at incredibly low cost. In time, you will be able to talk to a world-class oncologist about your cancer or have complex taxes filed for just a few dollars.

The costs of running all kinds of businesses will come dramatically down as the expenditure on services like software engineers, lawyers, accountants, and auditors drops through the floor. Businesses with real moats (network effect, brand, data, regulation) will become dramatically more profitable. Businesses without moats will be cloned mercilessly by AI and a huge consumer surplus will be created.

I think there will be a small handful of AI-enabled law firms or accountants or architects with the best technology that will service 80% of the market in each jurisdiction at a very low cost. There will be a few holdouts providing "handcrafted legal advice", but I think they will be the minority share of the market. We've seen this pattern in technology over and over again. The benefits accrue to a small handful of dominant companies which have an advantage in product or technology or distribution.

I don't know for sure whether these dominant players will be incumbents or newcomers in each industry. My guess is mostly newcomers. The ability to iterate quickly is overwhelmingly the most important factor in growing a successful business today, and big companies are too burdened down with thousands of people.

In the short and medium-term, I think it's very likely we see an explosion of indie hackers making $1m/year from side projects, with perhaps less need to raise VC funding.

I think the real winners in the immediate future will be those high-agency people who are good at noticing problems that people or companies have and then obsessively building solutions using the latest tools. One of YC's mantras is "Make something people want." Figuring out what people want will be a much more valuable skill once the "making" bit is freely available to all.

I also worry there's also a more distant, dystopian future where AI scours the world for any and all valuable ideas and quickly builds new startups to immediately capture that value. There may be no need for indie hackers or founders to even come up with ideas.

My main immediate worry in any of these futures is that the gains will accrue to a very small number of high-agency people who know how to use the new tools and build these new businesses. Lots of people who took low-risk whitecollar jobs are in for a huge shock. I don't say this gleefully; I am genuinely very worried and saddened by this possible future.

Will there be new jobs we can't yet imagine, or will everyone have practically unlimited free time? My bet is the former, although I don't know what the jobs are yet. I think it will result in incredible societal disruption until we figure out a new paradigm.

Figuring out how we distribute the world's resources in an age of intellectual (but not material) abundance is an unsolved question. There will still be limited resources. Property is finite. While we're still bound to one planet, so are physical resources. Electricity will be a limiting factor for a long time.

I'm extremely hopeful for the future. I think we may be able to cure basically every known disease. We may dramatically extend the human lifespan. This future could be very positive for humanity.

I'm also extremely worried. I think the short-term impact on hundreds of millions of people is going to be very profound, and I don't think many people are prepared.